Date and place

- March 9th to 10th, 1814 around Laon, a town in the Aisne department, Picardy, France (now part of the Hauts-de-France region).

Involved forces

- French army (37,000 men) under Emperor Napoleon I.

- Prussian and Russian army (90,000 men), under Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 6,000 to 9,000 men and 45 cannons.

- Allied army: less than 4,000 men.

Aerial panorama of Laon battlefield

The general situation

Although the battle of Craonne on March 7, 1814 was a victory for French troops, it also enabled the Allies to achieve their objective: to give Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher time to occupy his chosen position at Laon.

The town, which sits atop a steep and lonely 100-meters-high hill locally called the “Montagne de Laon” (Laon Mountain), is a natural fortress and is furthermore surrounded by walls .

Field Marshal von Blücher had approximately 90,000 to 100,000 men under his command, which decided him to attempt a decisive battle.

Napoleon I, for his part, also wanted a decisive battle, considering that, in his current situation, the success at Craonne had given him a moral ascendancy that he could only build on by continuing his offensive, despite the enemy's overwhelming numerical superiority. He had to act to keep the initiative.

The layout of the armies

Allied army

The Russian-Prussian forces were distributed as follows:

- 25,000 men on the right wing, on the west side, behind the village of Clacy [Clacy-et-Thierret] , under the command of Ferdinand von Wintzingerode ;

- 17,000 men in the center, commanded by General Friedrich Wilhelm Bülow von Dennewitz . They were supported by 50 cannons arrayed on the city ramparts, from the top of which they dominated the battlefield;

- 24,000 men on the left wing, led by Generals Johann David Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg and Friedrich Kleist von Nollendorf . They held the road to Reims, between the outskirts of Laon and the village of Athies ;

- Behind Yorck, the Prussians had a reserve of 25,000 additional men, formed by the corps of Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken and Alexandre-Louis Andrault de Langeron .

French Army

Napoleon, for his part, having driven an Allied rearguard from Urcel the previous evening, arranged his forces (25,000 men, not including Auguste Viesse de Marmont's 6th Corps, still absent at the start of the battle) as follows:

- on the left (west), General Henri François Marie Charpentier held the village of Clacy ;

- in the center, Marshals Michel Ney and Edouard Mortier were facing the suburbs of Sémilly and Ardon , respectively, from west to east;

- on the right, Marmont was awaited by the road to Reims, with almost 10,000 men.

The Emperor's intention, as expressed in his written orders, was to take Laon in a pincer movement, attacking from both right and left, with the center in support. This plan called for perfect synchronization of the two attacks. Unfortunately, Marmont was not on time for the rendezvous. Leaving Berry-au-Bac too late, he also stopped for a long time at Festieux , on the pretext of fog, and didn't leave until midday.

The battle

March 9th

Around 7 a.m., protected by a fog that concealed their small numbers, the French seized Semilly and Ardon with bladed weapons. They then came up against the main body of Blücher's columns, which brought up the rear with their artillery, blocking the attackers' progress. The cannonade continued for several hours until the fog lifted, revealing to the allies the small number of their opponents.

The Russians then attacked, with Ferdinand von Wintzingerode's corps climbing up to Semilly. The French retreated, surrendering the suburb and even the village of Clacy, a loss that would have serious consequences if the allies were able to cut off Napoleon's retreat by overturning the French left.

At the same time, von Bülow descended through the suburb of Ardon and pushed the French troops back onto the suburb of Leuilly .

By midday, the melee was general, except to the east, where Marmont was still expected. An hour later, the Emperor launched an assault on Clacy, but the Young Guard failed to take it, struck down by the enemy's powerful artillery.

Elsewhere, in the suburbs of Ardon and Semilly, fighting continued without the French managing to gain the upper hand over their opponents.

Fortunately for the Emperor's troops, the arrival of Marmont, finally signalled towards Athies, sowed doubt in the minds of the allied commanders: which of the attacks was the main one, which a diversion?

Taking advantage of this uncertainty, between 4 and 5 p.m., new offensives were launched under the command of Marshal Ney. The village of Clacy was recaptured, as was the suburb of Sémilly, but the Russian artillery's precision fire averted the danger of the French seizing the Porte de Soissons, which could have led to the fall of Laon.

On the Ardon side, the French, having recaptured the suburb, had to abandon it again, Blücher having finally decided to concentrate his efforts on this side.

At the end of the day, although the battle remained indecisive, Napoleon's only real success was the capture of Athies by Marmont's 6th Corps. Although his troops were mostly made up of young recruits and naval artillerymen, the Duke of Raguse had pushed back the Prussian front line at the foot of the Butte des Vignes [49.56494, 3.69492] and around the Mouillée Farm [49.56919, 3.71454]. He pushed it back to Athies, then forced it to evacuate the village, but was unable to prevent the Prussians from setting fire to it before leaving.

As night fell, the enemy withdrew to positions that had hardly changed during the day. Napoleon returned to his headquarters at Chavignon , without having completely abandoned his hopes of destroying Blücher's army. If his chances of victory were slim, he at least retained the initiative.

Night of March 9 to 10. The "Hooray" of Athies

Unfortunately for the French, during the night, the 6th Corps suffered a terrible debacle.

Having made the fatal mistake of bivouacking in the middle of the plain between Athies and the Lavergny Woods , rather than retreating to Festieux, and without sufficiently guarding its position, the corps was subjected to a surprise attack by Yorck and Kleist, while its leader slept soundly at the Château d'Eppes , a few kilometers away.

Panicking, the troop fled towards Berry-au-Bac , while their executioners chased them, shouting "Hooray!". The confusion was total. Marmont himself, rushing back, failed to rally his soldiers.

Two fortunate encounters save the fugitives. Firstly, a detachment of 400 horsemen, under the orders of Colonel Charles Nicolas Fabvier , returning after failing to liaise with Napoleon, who, by throwing themselves on the attackers, gave the sauve-qui-peut a chance to turn into a retreat.

Then there were some 125 hunters from the Old Guard. Arriving from Paris at Festieux during the day with a convoy of clothing, they took up arms on their own initiative to chase the Prussian cavalry out of the parade leading to the village, the only way of salvation for the fugitives. The survivors of Marmont's Corps finally rallied and withdrew to Corbeny and Berry-au-Bac, where they were no longer pursued.

However, French losses were terrible: 3,500 men out of action, 45 cannons and 120 caissons left in enemy hands.

March 10th

Unaware of the disaster, Napoleon rose at dawn the next morning, eager to resume hostilities. But the rout of the 6th Corps rendered his entire plan of attack obsolete. Nevertheless, he decided to press on, imposing his will on an enemy now in a position to destroy the entire French army.

Blücher, so often reckless, now lacked the audacity. Or perhaps his chief of staff, August Neidhardt von Gneisenau, was to blame, as the field

marshal may have been unwell that day.

In any case, when the Allied command realized that Napoleon was still there at dawn, apparently ready to attack, they called back the troops pursuing the 6th Corps, as well as the reserve of Sacken and Langeron, already on their way to Bruyères , in a move designed to attack the French army's right flank. These decisions, dictated by the moral ascendancy on which Napoleon had built, saved the Emperor.

Yet Napoleon still believed he could win. He calculated that to have defeated Marmont in this way, the allies would have seriously depleted Laon, and that an opportunity might present itself. That's why he was going to try a little harder. But although his conjecture was correct, the 40,000 or so men left in the town were more than enough to defend it.

Hostilities resumed at 9 a.m., with a Russian attack on Clacy . This assault, which was to be repeated five times, was repulsed, as were the following ones, by the "Marie-Louise" (conscripts of the 1814 and 1815 classes, called up in advance in 1813, most of whom were still beardless, hence the feminine nickname). The Russians even resumed the offensive in the early afternoon, but without success, as the Russian artillery continued to prove formidably effective.

In the suburb of Ardon, after having reached the foot of the Laon ramparts, Generals Claude Marie Meunier and Philibert Jean-Baptiste Curial were repulsed by von Bülow.

Acknowledging his failure, and seeing the return of the troops recalled by Blücher, which now deprived him of any chance of taking the town, Napoleon began to withdraw his own troops. The first convoys moved stealthily away towards Soissons at 3 p.m.; Charpentier withdrew via Mons , Anizy and Laffaux ; Mortier and the Guard via Chivy . In the evening, the rest of the troops followed, covered by a rearguard commanded by Marshal Ney.

The French lost between 6,000 and 9,000 men and over 45 cannons. Allied losses did not exceed 4,000 men.

The aftermath

The Allies let their opponents escape without taking any initiative, thus preventing themselves from completing their success by pursuing the French army. On the contrary, they remained inactive for almost two weeks.

Napoleon took advantage of this to achieve on March 13th his last success of the Campaign in northeast France at Reims.

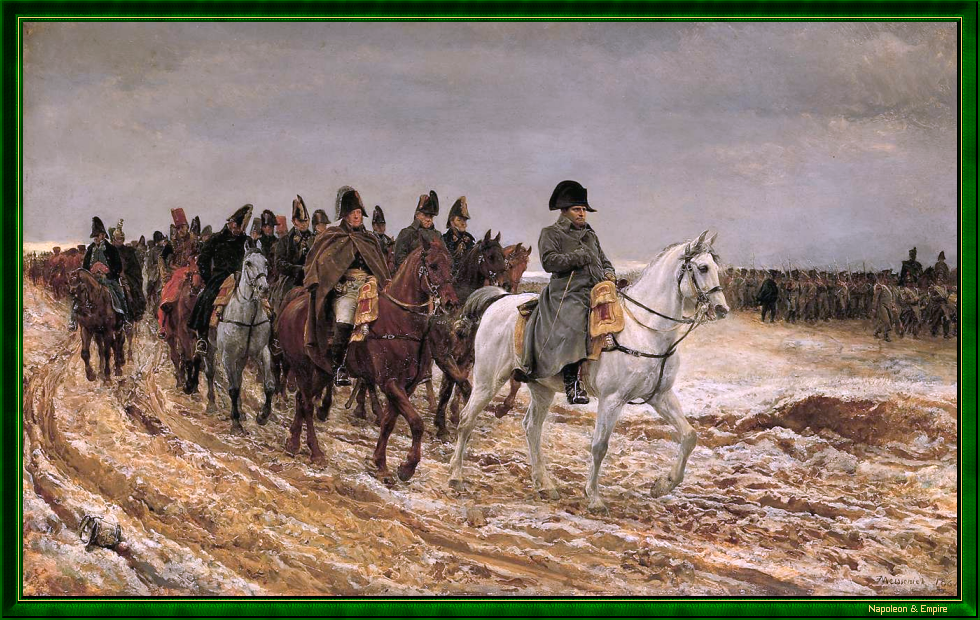

Picture - "Napoleon and Marshal Ney after the Battle of Laon". Painted 1864 by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier.

A commemorative plaque honors the valiant soldiers who fell on March 9 and 10, 1814 during the Battle of Laon.

Pronunciation: Laon is pronounced [lã].

Display the map of the Campaign in northeast France in 1814

Display the map of the Campaign in northeast France in 1814

Acknowledgments

The photo of the commemorative plaque of the Battle of Laon was kindly provided to us by Mr. Cyril Maillet.Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.