Date and place

- November 30, 1808 in the Somosierra (or Somo-Sierra) gorges in the Sierra Guadarrama, 90 km north of Madrid, Spain.

Involved forces

- French army (around 35,000 men, of whom 6,000 were actually engaged), including a brigade of Polish chevau-légers from the Duchy of Warsaw, under the command of Emperor Napoleon I.

- Spanish army (around 13,000 men, 8,000 of whom took part in the fighting) commanded by General Benito de San Juan.

Casualties and losses

- French army: fifty-seven Poles killed or wounded (out of one hundred and fifty who took part in the charge).

- Spanish army: between 200 and 2,000 killed, depending on the sources, 16 cannons, 10 flags.

Aerial panorama of Somosierra battlefield

The general situation

In early November 1808, Napoléon arrived in Vitoria [Vitoria-Gasteiz} in the Spanish Basque country, to take command of the French armies in Spain. His aim was to bring his brother Joseph Bonaparte back to the capital of his kingdom, which he had had to leave in a hurry on July 30, shortly after Pierre Dupont de l'Etang 's surrender at Bailén (July 22).

To do this, the Emperor had moved to Spain half the French forces in Germany, where he had a number of battle-hardened soldiers at his disposal. A series of Spanish defeats soon followed, putting the Emperor within reach of Madrid. Arriving from Burgos, he still had to cross the Central System mountain range (Sierra de Guadarrama, Sierra de Somosierra, Sierra de Ayllón), through which the road linking the two cities passed:

The battle site

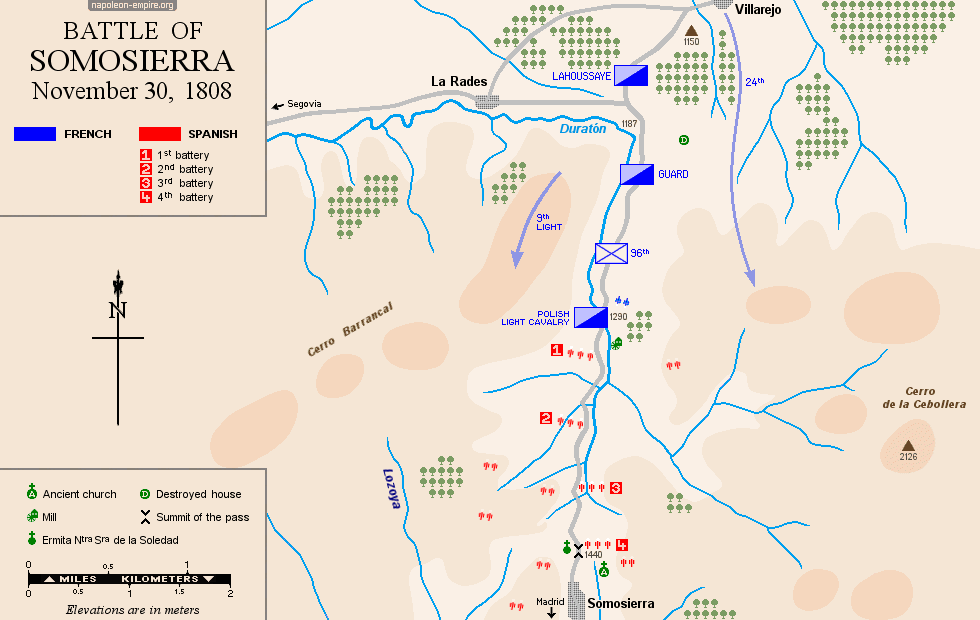

The obligatory crossing point was the Somosierra pass [41.13472, -3.58108], just before the village of the same name. A narrow, steep road led to it, forming a defile over the last six kilometers, which was easy to defend.

This was obviously the spot chosen by Spanish general Benito de San Juan to block the French route.

Of the approximately thirteen thousand men at his disposal, San Juan installed eight to nine thousand on the Somosierra heights, with twenty-two cannons distributed in four batteries staggered along the road .

Each battery commanded one of the main bends in the defile; the first shortly after a small stone bridge [41.15348, -3.58221] over the Duratón stream , the last, with a dozen guns, above the pass itself and a small chapel [today the hermitage of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad]:

First contacts

On November 29, at Boceguillas Napoleon was informed of the enemy's dispositions and came up against his vanguard at Sepulveda. After repelling an initial attack, the vanguard managed to escape under cover of darkness.

The next day, at 9 a.m., Napoleon ordered his infantry to advance. In thick fog, Marshal Victor sent three columns forward, one from the road, the other two from the slopes bordering it, the latter two to fall on the Spanish flanks. The easier terrain and poor coordination led the column that had taken the road to present itself alone in front of the first Spanish battery, which pinned it down.

The Polish charge

Around eleven o'clock, Napoleon arrived with his cavalry. He advanced towards the small stone bridge, observed the situation (the fog had lifted), and, noting that the infantry was unable to advance, ordered a cavalry charge.

All the authorities agreed that this was an impossible mission.

After a brief reconnaissance, a Marshal BerthierBerthier's aide-de-camp judged it to be such, Marshal BessièresBessières was opposed to the project, but Napoleon didn't care. In his anger, he uttered the historic words Impossible, impossible, je ne connais pas ce mot-là

(which, with success, became Impossible n'est pas Français

) and withdrew the mission from his Guard, entrusting it to the Polish squadron on duty with him that day.

The charge took place under the successive commands of squadron leader Jan Leon Kozietulski, captain Jan Dziewanowski and lieutenant Andrzej Niegolewski , who took it in turns to fall under Spanish fire without breaking the momentum of their comrades. Battery after battery was taken.

The Guards' mounted chasseurs are sent to the rescue, with squadron leader Andrzej Tomasz Łubieński taking command of the remaining Chevau-légers.

Meanwhile, frightened, the Spaniards began to abandon their positions. The first cavalrymen to arrive at the top of the pass found that most of their adversaries had fled, abandoning their weapons and baggage, massacring their general on the spot for having tried to hold them back (according to other sources, he died a victim of mutineers in Talavera on the following January 7).

However, a few of them remained around the last battery, inflicting two additional gunshot wounds and nine stab wounds on Lieutenant Niegolewski, who had already been badly hit during the charge but had courageously returned to his comrades. An emotional Napoleon presented Niegolewski with his own Legion of Honor cross when he arrived on the scene.

The charge lasted seven minutes.

Three more Polish cavalry squadrons ensured the pursuit, followed by infantry voltigeurs.

The aftermath of the battle

The road to Madrid was now open. Napoleon would enter on December 4.

The dead were buried with great pomp. The following day, at a review held in Buitrago, Napoleon uncovered himself before the survivors and declared: You are worthy of my Old Guard. I recognize you as my bravest cavalry

. No less than sixteen legions of honor were awarded.

Map of the battle of Somosierra

Picture - "Battle of Somosierra". Painted in 1810 by Louis-François Lejeune.

Lieutenant Niegolewski recovered from his wounds to write, forty-seven years later: May many young men have such a feast day

. Which goes to show that the notion of a holiday has come a long way since then...

The decision to send horsemen to assault a succession of artillery batteries has sometimes been seen as unjustifiable, even criminal. Some saw it as an illustration of Napoleon's disregard for the lives of his soldiers.

Aside from the fact that the event proved him right, since the charge did indeed achieve the hoped-for success, it's worth noting the assessment of English general William Francis Patrick Napier, unlikely to be biased in his favor, who took part in the Peninsular Wars and is regarded across the Channel as the best historian of these campaigns: The charge of the Poles, viewed as a simple military operation, was extravagantly foolish, but taken as the result of Napoleon’s sagacious estimate of the real value of Spanish troops, and his promptitude in seizing the advantage, offered by the smoke and fog that clung to the side of the mountain, it was a felicitous example of intuitive genius

.

A stained glass window in the Nuestra Señora de la Soledad chapel, depicting the Virgin of Czestochowa surrounded by Polish soldiers, was donated by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland and the Polish Embassy in Madrid in 2008, to mark the bicentenary of the battle.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.