Baron of the Empire

Pronunciation:

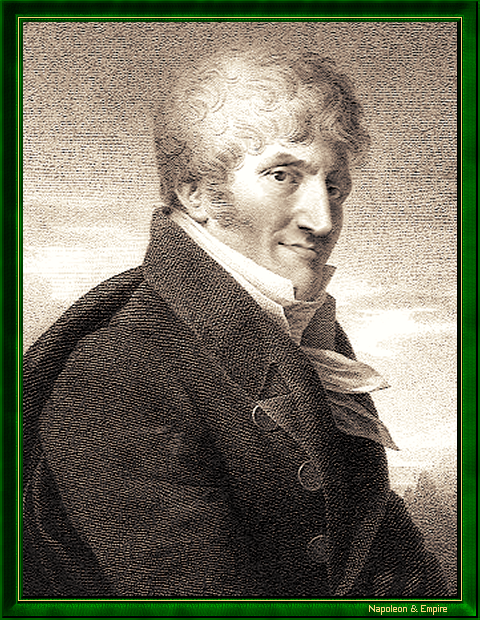

Edme-Joachim Bourdois de La Motte was born on September 14, 1754, at Joigny, in Burgundy. His father is a doctor and a corresponding member of the Royal Society of France. Vicq d'Azyr, founder of comparative anatomy and Marie Antoinette's physician, has rendered him a public homage.

Having completed his studies at the College of Auxerre, Bourdois, once obtained his Master of Arts, goes to Paris in order to do his medical studies. During these years, he shares with Jean-Nicolas Corvisart the narrow attic where they are housed. The two men become friends.

On February 11, 1777, Bourdois defends a first thesis. On March 6, a second one, the "cardinal", on a matter of hygiene. He proves that staying too long in contact with the heat during the winter period is harmful. He then submits the final two on issues of pure medical practice. In 1778, at the age of 24, he is a medical doctor.

He begins, in spite of repeated bouts of hemoptysis, a career as a physician at the hospital of Charity and doctor of the poor in the parishes of Saint-Sulpice and of the Gros Caillou.

In 1779, he became doctor of the Count of Provence, the future King Louis XVIII, and is quickly appointed physician of the Luxembourg Palace, and of the castle of Brunoy. He is also steward of the cabinets of physics and natural history, a position created especially for him. He is appointed regent of the medical school. He has his apartment in the Luxembourg Palace. In 1788 he is made first physician of Madame Victoire.

In 1793, Edme is declared suspect, arrested and jailed. Through the endeavors of his wife and constant intervention of Antoine Dubois, surgeon, board member of the armed forces and professor at the medical school, he finds freedom.

After the fall of Robespierre, Bourdois progresses in rank. He is informed by Dubois that a French expedition is preparing to reclaim Corsica, with René-Nicolas Dufriche Desgenettes at the head of medical services. The position of chief medical officer of the army of the Alps is vacant. Bourdois retrieves it on September 7, 1794 and deals more particularly the right wing. Annoyed, Bourdois faces a catastrophic reality: The small number of our former institutions in this division, the large number of patients who flocked at the same time, the absolute impossibility of evacuating by ground because of bad roads and by sea, for want of boats, have produced a significant bottleneck whose consequences would have been necessarily fatal if we did had anxious to prevent their effects. Between 1st of Vendemiaire and 1st of Ventose, 54,000 patients entered under the auspices of the army, and 5,300 died. From this calculation, it follows that, during these four months, one third of the army was scattered in hospitals, and that mortality can be assessed one-tenth of patients

. Having to face an epidemic of typhus, Edme Joachim takes emergency measures. He transports the sick in tents outdoors. He made clean, wash, ventilate the area of the barracks and train a team of paramedics. He distinguishes himself by an untiring dedication. He sets up hospitals, spacing them of three miles, and commandeers the convents and hospitals where patients with the disease are cared for night and day. A month later, the epidemic is under control. The morale of the men became good again.

Upon his return to Paris, Bourdois, sick in his turn, is threatened with arrest by the Directory. He is only just saved by Talleyrand.

At that time he is presented to General Bonaparte. The two men become great friends. During their walks in the countryside, Bonaparte regularly conducts Bourdois in the same valley. One day, the doctor asks to Napoleon why they come always to the same place. The general, stopping near a stream, says: This is where Caesar crossed the Rubicon!

On October 13 1795, Bourdois is dismissed after his resignation for health reasons from his position as chief medical officer of the army from the coast of Cherbourg. On October 26, 1795, Bonaparte asks him to take the role of chief medical officer of the Army of the Interior. The relationship between the two men is at its peak. Bourdois leaves the service of chief physician of the 17th military division of Paris on December 5 1796. In the aftermath of 13 Vendemiaire, Bonaparte, anxious, made fetch news of the doctor.

Relations between the two friends deteriorate when Bourdois declines the invitation to accompany Napoleon on his expedition to Italy. The General, turning to Bourdois, would have told him bluntly: You are one of us, I hope!

Seeing that his friend, taken aback, hesitates, Bonaparte, very susceptible, adds immediately: Never mind!

But the links between the two men are now distended. If Bourdois does not want to leave Paris, it is because of his profession, and especially of his wife's suffering, to whom he owes everything. The general, back from Italy then Egypt, will not want to see the doctor during almost fifteen years.

In 1805, the prefect of the Seine, Frochot, appoints Bourdois the rank of chief medical officer for the department of epidemics of the Seine. Its mission is to stop the epidemics that wreak havoc in the capital and surroundings.

In 1806, Bourdois, on government orders, supports an epidemic which has just declare at Lay, near Sceaux. He notes that the overt disease is encountered mainly among workers who work metals, among painters, potters and women who operate with white lead, a cosmetic which contains ceruse. Associated with basic preventive measures, Bourdois de la Mothe decides to use the treatment recommended in such circumstances in England.

He is appointed Inspector General of the University of France in 1809, then advisor of the University in 1811. That same year, at the behest of Corvisart, Napoleon gives him the charge of the first physician to King of Rome. Sire, said Corvisart to the Emperor, sacrify your reluctance to the interest of your son, a so precious head must be entrusted to Bourdois!

At the Tuileries Palace, in the same day, the Emperor announces to Bourdois: You are the doctor of my son! I can not give you a greater mark of confidence, do forget the past as I forget it myself!

On December 29, 1811, Bourdois is named Knight of the Legion of Honor. On February 27 1812, he is made knight of the Empire and then baron. His natural modesty refuses to wear the latter distinction. He became physician to the college of princes and consulting physician of the Emperor.

While it is devoted to the imperial son and provides him the best cares, Corvisart humiliates him one day, by questioning his work and by checking its validity. Bourdois is hurt but says nothing. Ten years later, Corvisart is dying. He sends for Bourdois for him to apologize.

When the Empire collapses Bourdois follows the Empress Marie-Louise and her son Napoleon II up to Blois. He does not resolve to leave his country. Under the Restoration, he returns to Paris and continues his private practice. He benefits from an affluent patient base. He also became physician in the Department of Foreign Affairs in charge of the navy and colonies. Louis XVIII appoints him his chief physician. Later, King Charles X does the same.

Why that longevity? Why such a presence in the royal medicine? He explains it by these simple words: I am far from claiming first place in the honorable art of medicine, but I claim to exercise it with this purity of intention, this love of humanity, I dare say more, this disinterestedness which only can render useful to men the lights, sometimes surprising, that we find in some doctors. My object is to be useful, it is my duty to relieve the miserable, my glory and my reward will be in the esteem of good men.

With his various works, Bourdois is accepted in all major scientific societies of his time. In 1806, he is associated ordinary resident of the Medical Society of Paris and honorary president of the Society of Medicine. In such title, he presents to the Emperor the respect and the wishes of doctors of Paris, in a speech he deigned to listen with indulgence and kindness.

He is admitted among the first at the Royal Academy of Medicine established in 1820. He is the president in 1822, 1823 and 1829.

Bourdois, 81 years old, died on December 7, 1835.

"Edme-Joachim Bourdois de La Motte", Burning of the nineteenth century.

His last work was for the Academy of Medicine where he completed in 1835, a report on Corvisart and his titles. His tribute, full of friendship, emotions and anecdotes, was a huge critical success in the medical world.

When he died, the Academy of Medicine suspended its work.

Bourdois had always shown great interest for testing of immunization against smallpox. He was admitted to a newly created company, the Society for the extinction of smallpox, and became president of the Central Committee of vaccinia. He even managed to get his friend Talleyrand, who became ambassador in London, a few samples of the vaccine which France was sorely lacking.