Date and place

- February 10th, 1814 at Champaubert, in Champagne, France (now in the Marne department, part of the Grand-Est region).

Involved forces

- French army (6,000 men) under Marshal Auguste Frederic Louis Viesse de Marmont, Duke of Ragusa.

- Russian army (4,500 men) under General Zakahr Dmitrievich Olsufiev.

Casualties and losses

- French Army: about 650 killed or injured.

- Russian Army: approximately 3,000 men killed, injured or prisoners, including General Olsufiev himself.

Aerial panorama of Champaubert battlefield

The general situation

After his defeat at La Rothière on February 1, 1814, Napoleon retreated first to Troyes , 40 kilometers to the west, then towards Nogent-sur-Seine, to the west-northwest, followed at a cautious distance by Generalissimo Karl Philipp Fürst zu Schwarzenberg.

Noting this adversary's lack of initiative, the Emperor then conceived a vast maneuver designed to destroy the Army of Silesia, commanded by Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, by far the most dangerous and enterprising of his enemies.

Blücher, who had broken away from the bulk of the Allies, marched directly towards Paris through the Marne valley, intending to push aside Marshal Etienne Macdonald's columns. At the same time, however, he was waiting for generals Friedrich Kleist von Nollendorf and Piotr Michailowich Kapzevich (Пётр Михайлович Капцевич) , who were arriving from Lorraine via the Châlons road. The result was a dangerous dispersal of his various corps. The Emperor noticed this mistake and resolutely took advantage of it.

Conceived by Napoleon on February 6 at the castle of Ferreux-Quincey [48.45081, 3.61346], the combination was immediately put into action. On the 7th, he set off, unafraid to leave just 20,000 men to face the bulk of the Austrian army. This bold move ensured that he had a troop whose strength was only slightly inferior to that of the Prussian general he was about to face.

After rallying Marshal Auguste Frederic Louis Viesse de Marmont in Nogent, the Emperor set off for Sézanne on the 9th, rushing towards a prey that had little idea of what lay ahead.

On that day, the Allies were arranged as follows:

- Johann David Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg was at Dormans and his vanguard at Château-Thierry;

- further south, Blücher, finally joined by Kleist and Kapzewitsch, had positioned them at Bergères-les-Vertus , while he moved his headquarters from Vertus to Etoges and pushed his cavalry as far as Meaux;

- Zakahr Dmitrievich Olsufiev (Захар Дмитриевич Олсуфьев) was in Champaubert , at the crossroads of the Sézanne road and the Paris-Châlons road [48.88089, 3.7758889];

- Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken , some fifteen kilometers further west, was at Montmirail and his vanguard at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre

This system, despite an effort to tighten it attempted in the last few days, remained too scattered (Blücher and his cavalry were separated by almost 80 kilometers) to enable the various corps to support each other effectively in the event of an attack.

This was because the Allies hardly believed it was possible, and imagined that, should it nevertheless take place, they would have all the time needed to deal with it. Wasn't Napoleon still in Troyes on February 5, nursing his defeat of the 1st, trailing a much stronger opponent? How could he consider weakening himself further by sending a detachment to the river Marne?

What a surprise, then, on the evening of the 9th, when Napoleon's vanguard came to disrupt the Prussian headquarters. The latter was immediately withdrawn to Vertus, where Blücher learned the next morning from a courier from Schwarzenberg that the Emperor, accompanied by the bulk of his forces, was on his way to attack.

Blücher immediately changed his plans and ordered Sacken and Yorck to join forces at Montmirail the same day. But both had already set off to join their respective vanguards at Château-Thierry and La Ferté-sous-Jouarre. Having been warned too late, they were unable to make the rendezvous.

For his part, Blücher himself marched right up to the contingent in front of him and pursued it towards Fère-Champenoise , hoping to dissuade the enemy, whom he believed to still be in Sézanne, from pushing on to Montmirail. He flattered himself that this would give his two generals time to reunite.

But all his calculations were wrong, as Napoleon had already attacked Olsufiev at Champaubert .

The battle

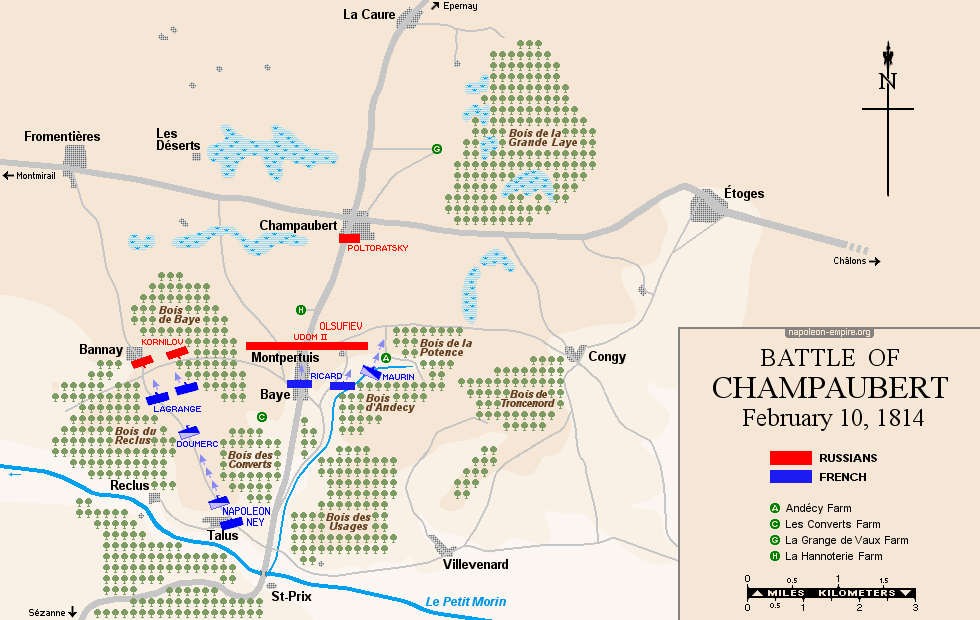

The Russian general's forces were concentrated around the villages of Champaubert , Baye and Bannay , the latter of which was not strongly occupied.

Marmont's troops arrived from the south, crossing the Petit-Morin at Talus Saint-Prix , where Olsufiev had failed to guard the bridge [48.82417, 3.75350], and the first French cavalrymen came up against the Russians at Bannay at dawn.

The Russian general sent 6 of his 24 cannons and four regiments to retake the bridge. But it was already too late. Marmont's entire corps had crossed and taken up positions around the road leading to Champaubert via Baye. The Russian regiments were forced to fall back towards Baye, where they occupied the woods surrounding the village. Their artillery was brought into action to the southwest of the village, near Les Converts [48.85006, 3.75580]. Informed that his regiments were facing a full-scale attack, Olsufiev soon sent two brigades and the bulk of his artillery to reinforce them.

The battle remained indecisive throughout the morning, until Marshal Michel Ney and Napoleon arrived around midday at the head of two additional divisions. The artillery went into action in front of Bannay, while Marmont attacked the village of Baye, which was taken at around 1:30 pm.

General Olsufiev was unable to withdraw in the face of forces superior to his own, or to warn his general-in-chief that he had to give battle. He thus deprived himself of the support that Kleist and Kapzewitsch, who were not so far away, could perhaps have given him. This attitude was all the more surprising in that his numerical inferiority was compounded by the lacking of any cavalry, which his leaders had judged to be more useful to the vanguard. The battle seemed lost in advance.

Olsufiev, against the advice of his generals, nevertheless decided to hold the position.

The Russian troops then organized themselves in a very long line stretching from Baye Wood on the right (west) to Malet Wood and Andrecy Farm on the left (east), passing through Hannoterie Farm and the hamlet of Montpertuis . To the rear (north), a single brigade, with some artillery, was tasked with holding Champaubert at all costs.

Despite the width of the front, the French tried and succeeded in overrunning it on both sides: on the right (east), through the Potence Wood ; on the left (west), by finally dislodging the Russians from Bannay, at the cost of repeated attacks. It was around 3 p.m.

Then the Emperor sent his cavalry, whose terrain was ideal, to turn the enemy through Fromentières to the west. The latter had no choice but to fall back on Champaubert, which was firmly held.

This time, Olsufiev decided to retreat. His first move was to head east towards Etoges, but he found the road cut off by the French. He then turned back towards Montmirail, but came up against the cavalrymen sent to Fromentières earlier by the Emperor. His troops were scattered and fled northwards, partly towards La Caure , partly towards the Grande Laye Wood .

Only the brigade occupying Champaubert was still holding out. It was soon attacked. Hand-to-hand fighting was furious. The Russians defended every house foot to foot. In the end, however, they surrendered, their ammunition exhausted, after trying in vain to force their way through the encircling French troops. Their losses exceeded a thousand men.

As night fell, the fugitives, who had first rallied and marched north towards Epernay , turned south-east towards Etoges. But it was not to their liking. Marmont, who had been entrusted with the pursuit, sent his infantry and cavalry into action on the Bois de la Grande Laye and the Grange de Vaux farm , causing panic in the Russian ranks.

Totally disorganized this time, hundreds of them fell into the hands of their victors or drowned in the Désert ponds. Olsufiev himself and his staff were taken prisoner. Only around 1,500 of the 5,000 men in his corps finally managed to reach Etoges and the allies.

The aftermath

The victory immediately restored Napoleon's over-confidence. He saw it as a brilliant change in his position, proof that his Star had begun to shine again in all its glory. As an immediate consequence, he sent orders to General Armand de Caulaincourt, in the midst of peace negotiations with the Allies, to adopt a less accommodating attitude.

Map of the battle of Champaubert

Picture - "Emperor Napoleon the evening after the Battle of Champaubert, February 10th, 1814". Painted by Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet.

That same evening, Napoleon invited General Olsufiev and his staff to dine at his table in the Maison Bleue or Maison au Boulet (where a cannonball is embedded in the façade ). He then spent the night there.

Opposite the Maison Bleue, a column surrounded by eight cannons has been erected to commemorate this victory.

Olsufiev's stubborn refusal to retreat may well have been the result of Blücher's harsh comments to him after the battles of Brienne and La Rothière.

Display the map of the Campaign in northeast France in 1814

Display the map of the Campaign in northeast France in 1814

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.