On the eve of the 18 Brumaire18 Brumaire, the army, almost the only one to escape the general decadence of the institutions that characterized the end of the Directoire, retained its prestige and solid organization. Napoleon Bonaparte, the most glorious of its leaders, found powerful support there to seize power. But very quickly, his policy of rallying support from the general public offended the sensibilities of a body that was still very attached to revolutionary symbols.

An overly conciliatory policy

The abolition of the January 21st holiday (the anniversary of Louis XVI's execution), the end of the hostage law, the choice of certain consuls and ministers - all these decisions, taken in the space of a few weeks in a spirit of reconciliation, were either not understood or poorly accepted by the army, at least by the senior military hierarchy.

Nevertheless, the government was extraordinarily popular. Its action met the expectations of most of the population, who wanted peace, the return of religion and the certainty of keeping the national assets acquired during the Revolution. But these objectives required agreement with the Church, which the elites, and in particular certain army officers who were militantly anti-clerical, did not want.

But the Ideologues' republican opposition did not undermine the government's authority. On the contrary, the Rue Saint-Nicaise bombing and the battle of Marengo, skilfully used by propaganda, further strengthened the First Consul's popularity. He took advantage of the situation to lay the groundwork for the Concordat, which was finally approved shortly after the Peace of Amiens.

A worrying development for the regime

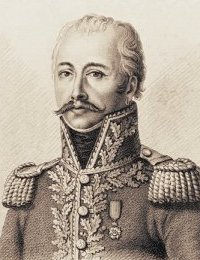

This new success for the executive, which gave Bonaparte undeniable moral authority, was not enough to quell the generals' discontent. On the contrary, they took advantage of the Te-Deum organized to celebrate the signing of the Concordat on April 18, 1802, to show their disapproval by their poor dress. Forced to attend by order, they took their revenge with loud, insulting murmurs against the Church, the parish priests and even the First Consul, disrupting the ceremony with their saber-rattling and boot-snapping, their mockery and their refusal to give up the seats reserved for ecclesiastics. Jean Victor Moreau, for his part, dispensed with attending the solemnities and showed himself off to the Parisians on the Tuileries terrace, smoking a cigar while mass was being held. That same evening, General Antoine-Guillaume Delmas, to whom Bonaparte expressed his delight at the success of the festivities, had no hesitation in retorting: A fine capucinade, indeed; all that was missing was the hundred thousand men who got killed to put an end to it all!

It was clear, then, that the high command was on the verge of tipping over into opposition, and that its growing irritation could soon lead certain generals to envisage extreme measures. Bonaparte knew that the idea of a coup had already been floated, and that only his popularity and authority had so far dampened the ardor of the discontented. Some of them have already been removed or will soon be. Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte was in command at Rennes, Etienne Macdonald had been ambassador to Denmark and Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr to Spain since 1801, General Delmas was exiled thirty leagues from Paris shortly after his scathing repartee, and Guillaume Brune was appointed to Constantinople in September 1801.

The institution of the Legion of Honor and the vote in May 1802 to make the Consulate for life further strengthened military opposition. They saw it as an infringement of the principle of equality, a first step towards re-establishing a monarchy and nobility for Bonaparte's benefit. To them, the legacy of the Revolution and the republican form of the regime were in danger. What's more, the army, in a country at peace for the first time in ten years, was not happy about what it saw as a loss of influence.

The plot

In May 1802, the authorities noticed that vehement pamphlets aimed at the military, both active and reserve, were spreading throughout the capital. These included Appel aux armées françaises par leurs camarades and Adresse aux différents corps et militaires réformés.

A police investigation revealed that Paris was not the only city where these texts were circulating, but that they could be found in several other provincial cities, particularly in the western départements. They were transported in stoneware jars normally used to store and transport butter. Investigations eventually revealed that the printing works from which these libels originated was located in Rennes, where Bernadotte was in command.

All the investigations, those of Joseph Fouché's General Police and Louis Nicolas Davout's Military Police, those of Louis Nicolas Dubois, the Prefect of Police of Paris, and Jean-Joseph Mounier, the Prefect of Rennes, led to the same conclusion: the author of the pamphlets belonged to the staff of Désirée Clary's husband.

Fouché, a friend of Bernadotte's, sought to protect him by diverting the investigations to the Chouans, but Mounier, going beyond his instructions, identified the real writer as General Edouard-François Simon, chief of staff, assisted by second lieutenant Bertrand. Simon, claiming full responsibility for the affair, declared that he had planned to provoke an uprising of Republican officers, and to enter Paris at the head of reliable troops, in order to proclaim the deposition of the First Consul, who had previously been arrested.

Despite this confession, Bonaparte had no doubt that Simon was merely protecting his leader. The latter, opportunely unwell, left his post to take the waters at Plombières, while his subordinate was incarcerated in the Temple prison. For a time, Bonaparte thought he could implicate Moreau as well. Indeed, among the recipients of the first shipments was one of his close friends. But the victor of Hohenlinden refused to respond to the police and adopted a defiant attitude towards them. He played down the affair, derisively calling it the "butter pot plot".

Moreau: the dangers of ambiguity

But his position was not as solid as he thought. He had already made his first political error, a few years earlier, when, having come into possession of Jean-Charles Pichegru's correspondence with Austria, he withheld it for several months before passing it on to the Directoire. Accusations of royalist sympathies followed. In 1799, he was reluctant to act as sword for Emmanuel Siéyès, even suggesting the name Bonaparte. Since then, his ambitions have grown, and his victory over the Austrians in December 1800 made him a credible rival to Bonaparte. Bonaparte initially sought to win Moreau over to his cause, first by arranging for him to marry his sister Caroline and then his adopted daughter Hortense de Beauharnais. But Moreau preferred to marry Mademoiselle Hulot, a Creole who was jealous of Joséphine and scared her. As a result, their family circles drove the two men apart, especially as Moreau had become a rallying point for Republican generals. What's more, he held a salon, where he engaged in acerbic criticism of Bonaparte before a select group of liberal guests. The First Consul was well aware of this. Esteem gradually gave way to irritation, then to animosity, and the rupture began. Moreau's stance on the Concordat and the Legion of Honor consummated the divorce.

However, Moreau's imprudence and lack of political sense prevented him from becoming the central figure of a republican opposition. He immediately squandered this opportunity, which worried Bonaparte, by renewing relations with Pichegru, who was busy fomenting a plot against the regime and its leader. This mistake gave the First Consul the opportunity to disqualify him. His equivocal attitude during the Cadoudal conspiracy marked his political ruin and led to his exile.

After this episode, the Jacobin generals were left to ponder the fate of their friend, until the reignition of war changed their thinking and diverted their energies towards objectives more suited to their abilities.

With the parliamentary opposition already wiped out, there is no longer any constituted opposition.