Date and place

- September 8th, 1796 at Bassano del Grappa, in Venandia (nowadays province of Vicenza, Italy).

Involved forces

- French army (19,500 to 23,000 men, depending on the source) under the command of General Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Austrian army (16,000 men) under the command of General Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 400 men out of action

- Austrian army: 600 men killed or wounded, 3,000 prisoners, 35 cannons, 5 flags.

Aerial panorama of the Bassano battlefield

The Battle of Bassano saw the French army commanded by General Napoleon Bonaparte rout the Austrian forces of Alsatian General Dagobert Sigismund von Wurmser.

General situation

Following his defeat at Castiglione on August 5, 1796, Wurmser withdrew to the Tyrol, where his forces were soon replenished. The Austrian government decided to make another attempt to rescue the city of Mantua [Mantova] , which had been under French siege since June 1796.

To this end, Wurmser set off down the Brenta river valley with 26,000 men to invade the Po plain. He left behind Paul von Davidovitch and 20,000 soldiers in the Tyrol. Their mission was to catch the French from the rear if Napoleon Bonaparte advanced to meet Wurmser.

On the contrary, the French general-in-chief marched on Davidovitch, pushing him back beyond the entrance to the Brenta valley, and entered the valley in pursuit of his Austrian counterpart. The latter, instead of continuing on his way in accordance with his plan of operation, stopped, for reasons that are unclear, to wait for his enemy.

Preliminaries

On September 7, the Charles Augereau division captured three Croatian battalions at Primolano, which had been left there to liaise with Davidovitch's forces. Despite stubborn resistance first in the village, then in the shelter of a fort at Covolo [Covolo del Butistone], these 1,000 to 1,500 men were forced to lay down their arms.

In the evening, the French bivouac at Cismone [Cismon del Grappa]. Bonaparte was among them. Meanwhile, the André Masséna division, arriving from Trento , joined the rest of the army.

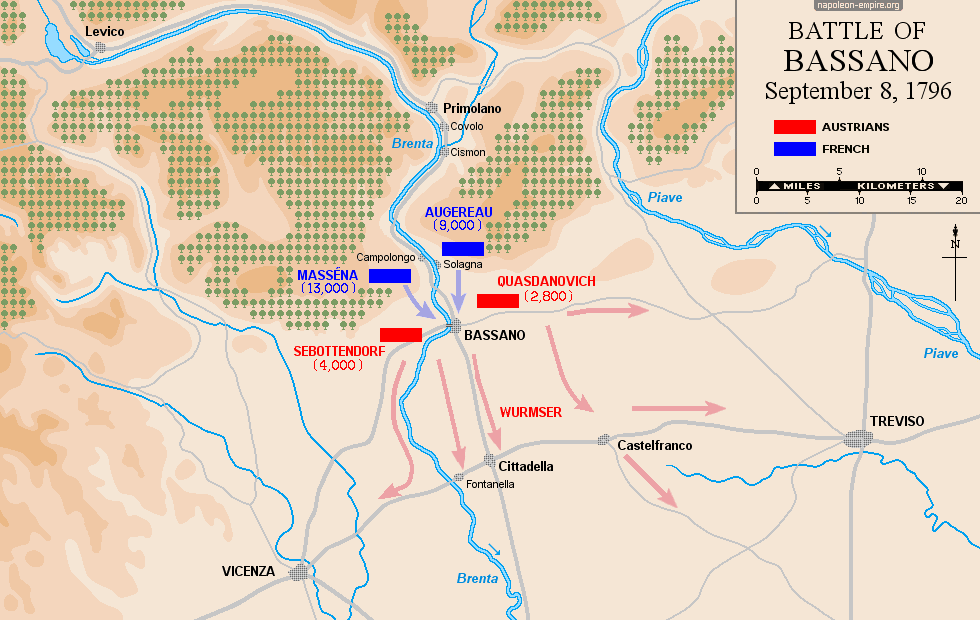

Positions and manpower

Wurmser set up his headquarters in Bassano del Grappa . The town lied on a plain not far from the exit of the Brenta Gorge, on the left bank of the river.

The Austrian general-in-chief positioned his troops, comprising the Peter Vitus von Quasdanovich and Karl Philipp Sebottendorf divisions, on both sides of the river, a little upstream. Six battalions set up seven kilometers further on as a first defensive curtain:

- Three were stationed at Campo Lungo [Campolongo sul Brenta] under the command of Colonel Jacob Revertera von Salandra on the western side of the valley;

- The other three, commanded by Adam Bajalics von Bajaháza (Bayalitsch), protected the eastern side at Sologna.

Taken together, they blocked the gorge, which was always very narrow at this point.

The Austrian vanguard, under Johann Mészáros von Szoboszló , was too far away to intervene. It was now well beyond Vicenza. Urgently recalled on September 7, it was still only at Montebello Vicentino on the 8th. Wurmser therefore had only around 16,000 men available to take part in the forthcoming battle. His decision to fight under these conditions seems incomprehensible.

During the night, Wurmser ordered his artillery and bridge crews to leave the front line and establish themselves at the junction of the Cittadella and Castelfranco roads. Here, the Brenta can be forded, making the road to Vicenza and Mantua just as safe as the Bassano bridge [45.76753, 11.73116] .

Bonaparte had around 20,000 men at his disposal, belonging to the Augereau and Masséna divisions. They descended the gorge as fast as they could.

The battle

The exact circumstances of the battle remain very unclear. Sources lack clarity and, what's more, diverge. It is therefore difficult to form a precise idea of the sequence of events. The general impression is of a furious onslaught by French troops that swept away everything in its path.

On September 8, 1796, the French army set off at 2 a.m. to surprise the Austrians with the suddenness of its advance (80 kilometers in just two days).

At seven o'clock, the French came into contact with the enemy rearguard. Augereau threw himself onto the left bank of the Brenta River, with the exception of one of his half-brigades, which preceded the Masséna division on the right bank. Confident in the strength of their position, the Austrians attempted to resist. However, they were dislodged.

Joachim Murat's cavalry ensured the pursuit. A good part of Revertera's unit was taken, including his colonel. Bajalics' troops withdrew more quickly, but their leader also fell to the French.

The fugitives fled, some towards Quasdanovitch and Sebottendorf's units, others towards Bassano. They spread panic everywhere. Behind them came the French. The Austrians gave in without putting up their usual resistance and took refuge in Bassano, with the enemy hot on their heels.

Augereau entered the city from the east. Masséna seized the cannons defending the bridge, crossed it and entered the city from the west, knocking out the enemy grenadiers trying to protect the headquarters.

An incident brought the Austrians' confusion to a head. Instead of withdrawing to Cittadella as ordered, their bridge crews and artillery, due to a misunderstanding, clogged up the city's exits.

However, Quasdanovich and Sebottendorf's troops seemed to have managed to join up south of the city. But the Masséna division caught up with them and disorganized them once again. The Austrian retreat turned into a stampede.

After retreating to Cittadella , Wurmser tried to re-establish a semblance of order, then headed west on the road to Fontaniva , where he crossed the Brenta . Some of his army's baggage managed to rejoin him, while others escaped to Castelfranco to the east, but most of it was caught by French cavalry.

The Quasdanovich division, for its part, cut off from the main body and overwhelmed on its western flank, was forced to flee to Friuli, Venetian territory to the east of the City of the Doges.

Results

The day was not very bloody. The Austrians suffered only 600 dead or wounded, the French 400 at most. On the other hand, the Republican army took 3,000 prisoners and large quantities of equipment: 35 cannons with their caissons, two bridge crews, five flags and two hundred vans.

Consequences

Wurmser's army was totally disorganized, its communications with the Tyrol cut off and its strength reduced to 14,000 men. The Austrian general decided, however, to continue advancing to bring the war to the vicinity of Mantua, after rallying Mészáros's troops.

Bonaparte, for his part, now wanted to force Wurmser to surrender or, failing that, to throw himself into Mantua. What forces remained in the Austrian general's favor would then be of little concern to the French. The two armies immediately began a pursuit that would end on September 15, when Wurmser locked himself in the town for good.

Map of the battle of Bassano

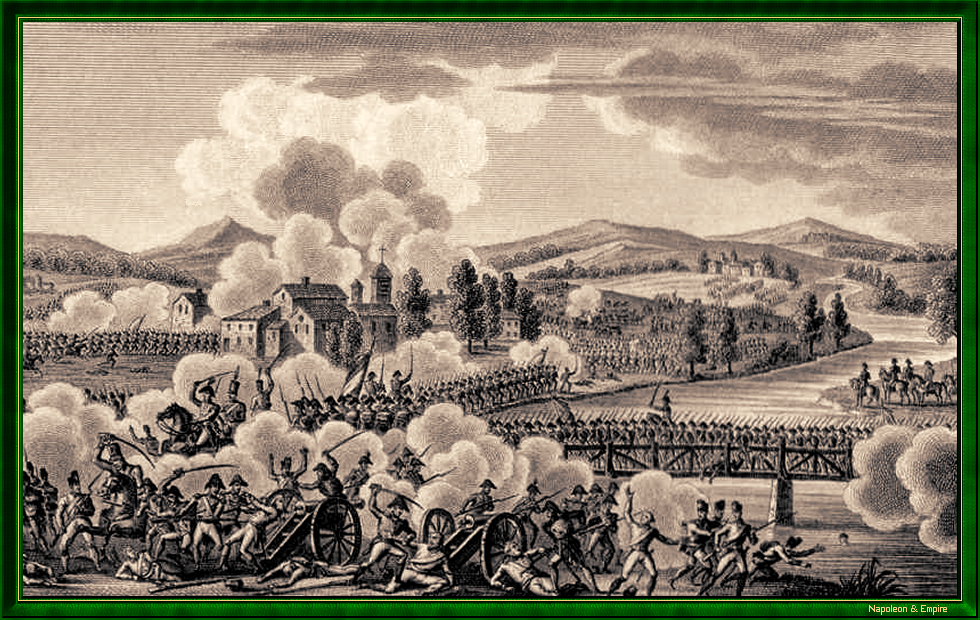

Picture - "Battle of Bassano". Drawn and etched by Louis François Couché son (1782-1849), finished by Edme Bovinet (1767-1832).

In his Memoirs, Napoleon recounts how, on the eve of the battle, exhausted and starving in the bivouac at Cismone, he owed his food to the kindness of a soldier who offered him a portion of his ration. This generous donor brought him back to the Boulogne camp in 1805. History does not say how the Emperor repaid this debt.

Display the Map of the First campaign in Italy (1796-97)

Display the Map of the First campaign in Italy (1796-97)

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.